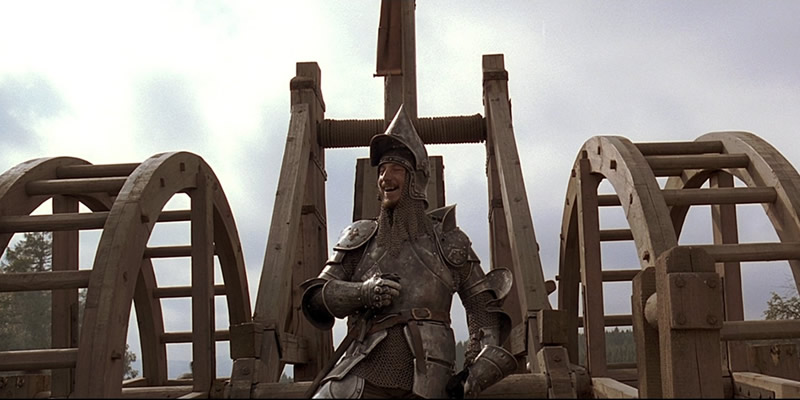

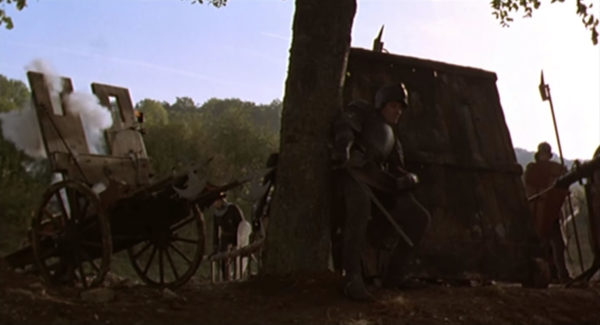

We know a lot about Joan of Arc including that she besieged cities with cannons, not trebuchets. Yet, when it came time to showcase Joan’s army using siege weapons in The Messenger: The Story of Joan of Arc (1999), director Luc Besson went with a siege tower and a trebuchet.

It’s easy to let this medievalism slide, but the filmmakers were so insistent on their historical accuracy in the DVD’s featurette: The Messenger: The Search for the Real Joan of Arc. In this 30-minute documentary, actress Milla Jovovich assures us that they

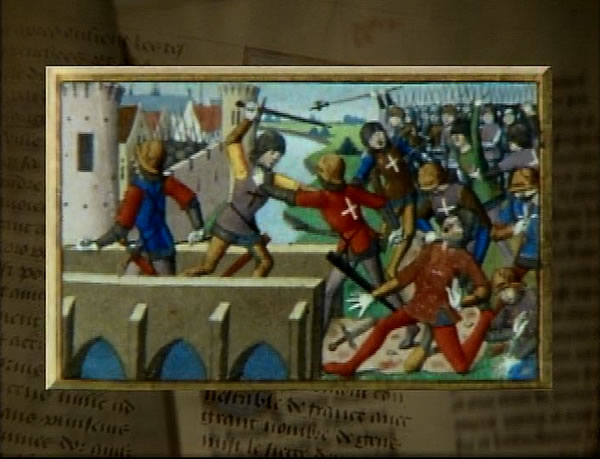

meticulously scoured the national archives. Using these extremely rare illustrated manuscripts, which were the newsreels of the day, the filmmakers were able to recreate with exact detail the fortresses, weaponry, and troops involved in the actual battles.

As Jovovich says this, the documentary flashes images from a medieval manuscript. These images include armored men with swords, bows and arrows, and ladders scaling up city walls.

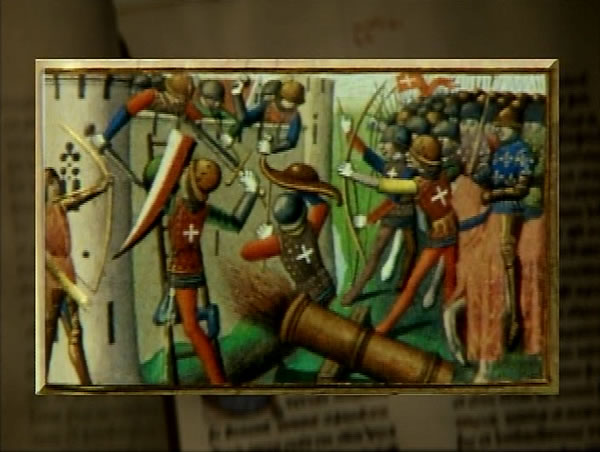

Among these images are numerous depictions of cannons.

All of the manuscript images in this montage come from Martial D’Auvergne’s the Vigil of Charles VII between 1477 and 1483. This lavishly illustrated manuscript was published in 1484, well after the events of 1429-1431. ((Estelle Doudet, “Martial d’Auvergne”, in Encyclopedia of the Medieval Chronicle, ed. Graeme Dunphy (Leidon: Brill, 2010), 2:1083-1084.))

That the filmmakers supposedly studied this manuscript and walked away with trebuchets is baffling. Out of the 192 images in the manuscript, more than 150 of them depict troops battling, besieging, marching, accepting surrender, or standing guard. Of those, 29 feature cannons. More importantly, there is not a single trebuchet depicted throughout the entire Vigil of Charles VII. Don’t believe me? Take a look for yourself.

The filmmakers would have had plenty of material outside this work, as Joan of Arc is a popular figure and the primary military engagement of the movie—the Siege of Orléans—shares in this popularity. As medievalist Kelly DeVries puts it,

No single military engagement in the Hundred Years War has had more written about it than the siege of Orléans, and primarily the relief of that siege by the French army. The battles of Crécy, Poitiers, Agincourt, Formigny, and Castillon together cannot together boast the number of pages devoted to the siege of Orléans. ((Kelly DeVries, Joan of Arc: A Military Leader (Phoenix Mill: Sutton, 1999), 53.))

Contemporary histories tell us that “gunpowder bombardments were exchanged between the city and the English almost daily.” ((DeVries, Joan of Arc, 56.)) As for Joan, DeVries succinctly points out that she “lived in an age of gunpowder weaponry use” and that “gunpowder weapons played an enormous role in Joan of Arc’s military career. At every conflict she was witness to the massive destruction they could cause; she fought successfully against them, and she fought successfully with them.” ((Kelly DeVries, “The Use of Gunpowder Weaponry by and against Joan of Arc During the Hundred Years War,” War & Society 14, no. 1 (1996): 1, 14.))

DeVries and the contemporary histories of Joan’s time are not alone. For example, Clifford J. Rogers identified a military revolution of sorts occurring between 1400 and 1430 among the English and French during Hundred Years War in the realm of artillery. The effectiveness, size, and prevalence all increased rapidly during this time, which meant “gunpowder artillery overturned the centuries-old dominance of the defensive in siege warfare.” ((Clifford J. Rogers, “The Military Revolutions of the Hundred Years’ War,” The Journal of Military History 57, no. 2 (1993): 266, 272.))

Previous cinematic depictions of Joan of Arc and cannons

Remarkably, the filmmakers cannot point to previous films for their lack of cannons. A brief survey of previous cinematic depictions of Joan of Arc in battle demonstrates that her associations with cannons is not some new revelation. Prior to the release of The Messenger, Jacques Rivette’s low-budget Jeanne la Pucelle (1994) has cannons of different shapes and sizes, as well as a full-blown cannonade before an assault.

Prior to that, Victor Fleming’s big-budget Hollywood Joan of Arc (1948) prominently depicted cannons on both sides of the Siege of Orléans.

Even Cecil B. DeMille’s 1917 silent film Joan the Woman sports cannons among the soldiers attacking a castle wall.

So why use a trebuchet instead of cannons?

In the same documentary available on The Messenger DVD, a narrator tells us that “director Luc Besson assured that the experience was frighteningly real,” which “really helped Milla Jovovich get inside of Joan.” The documentary then cuts to an on-the-set interview with Jovovich out of character explaining

You don’t understand Joan until you see that, until you experience the terror of men killing each other all around you. Then you see what this little girl really felt like. She came in with all these ideas in her head and she changes when she comes out. And I did too. I mean, I’ve never been through anything like that. It was very frightening. Very frightening.

With such an emphasis on the desire to “recreate with exact detail … the actual battles,” why use a trebuchet instead of cannons? Wouldn’t the boom and smoke of medieval gunpowder add to the “frighteningly real” experience?

The lack of gunpowder was obviously not due to a lack of historical knowledge or cinematic precedence. Instead, the filmmakers are exposing a bigger theme prevalent in cinematic medievalism that numerous historians have addressed—depicting what feels authentic to the audience is different than depicting what is accurate. The audience will accept the former well before the latter. ((Martha W. Driver, “What’s Accuracy Got to Do with It? Historicity and Authenticity in Medieval Film,” in The Medieval Hero on Screen: Representations from Beowulf to Buffy, eds. Martha W. Driver and Sid Ray (Jefferson: McFarland, 2004), 20.))

One blatant example is how movies often depict a medieval building as old as it might look today, as opposed to freshly built as it would be in the film’s historical context. ((Bettina Bildhauer, “Medievalism and Cinema,” in The Cambridge Companion to Medievalism, ed. Louise D’Arcens (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2016), 50.)) Then there is the ball and chain, a post-medieval concoction that appears in almost every medieval film including The Messenger. Also consider that “many popular medievalisms are about the rejection of technology,” ((Laurie A. Finke and Martin B. Shichtman, Cinematic Illuminations: The Middle Ages on Film (Baltimore: The John Hopkins University Press, 2010), 15.)) which in this case is gunpowder.

As such, modern viewers are more ready to accept heavily-armored knights fighting alongside a trebuchet than with gunpowder. With its reliance on gravity, the trebuchet is a purely medieval machine—invented, evolved, and retired all during the Middle Ages. Joan of Arc fits squarely within popular culture’s notion of medieval, so why risk tarnishing that with cannons?

Even with historical, academic, and cinematic precedence of Joan of Arc using cannons, the filmmakers rejected technology and went with what felt authentic instead of what was accurate.